Lady in the lake murder: Why reporter has returned to the crime 27 years on

On a warm summer day, three amateur divers broke the surface of Coniston Water in Cumbria, pulling behind them a canvas package trussed up with rope.

The package was heavy but they managed to drag it ashore. With a knife, one of the divers cut through the canvas cover. Pieces of lead fell out.

The men recoiled. Inside was a body.

That evening, detectives stood on the edge of the lake. The crime scene was illuminated by high-powered lamps. They peered down at the grim remains of a young woman.

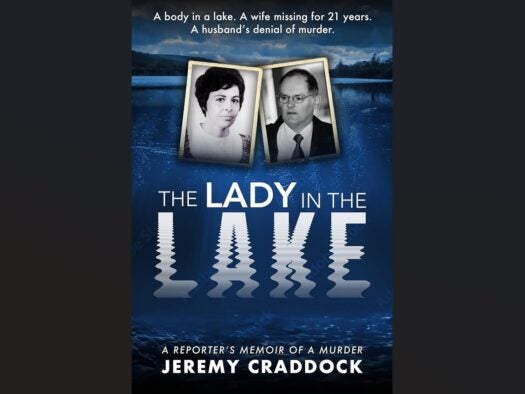

The year was 1997. I was a young reporter on the local newspaper, the Westmorland Gazette, one of the first journalists to cover the case. More than a quarter of a century later I have written The Lady in the Lake: A Reporter’s Memoir of a Murder.

The body was that of Carol Park, a 30-year-old mother from Barrow-in-Furness. Her body had lain in its watery grave for 21 years.

Writing the book was a challenge. How could I justify returning to an old case, one that was within living memory? Was it in the public interest?

These were questions I wrestled with as I dug into the archives and interviewed key figures from the original investigation. I knew at some point I would have to approach the victim’s family.

It is a book about a terrible murder but it is also a rumination on the ethics of writing true crime and a portrait of a bygone era of pre-internet newspapers.

The landscape of crime reporting has altered irrevocably since 1997. The Leveson inquiry in 2012 put an end to unethical practices such as hacking the phones of murder victims like Milly Dowler. It also forced the industry to examine its conscience on past behaviour, resulting in a more sensitive attitude generally to how crime is reported.

At the time, Guardian crime correspondent Duncan Hamilton worried that Leveson’s impact would lead to a chilling of relations between journalists and the police, making it difficult for crime reporters to do their job.

It is true that reporters no longer enjoy the same level of direct contact with the police as they once did due to the control of press officers. But I believe a gradual move towards an ethical mode of crime writing is welcome.

Yet there is more to be done.

Prime suspect and miscarriage of justice claims

We saw the rapacious pursuit of salacious details following the disappearance of Nicola Bulley in 2023 by self-appointed social media ‘detectives’ with little or no understanding of press ethics or the damaging impact of their actions.

Since Leveson, there has been a strengthening of the IPSO code with new guidance in areas such as reporting suicide (clause 5), the addition of mental health to privacy (clause 2) and greater protection of children accused of committing a crime (clause 9). This has certainly contributed to a new sensibility around crime reporting. But there are some commentators who believe the industry should go further.

Former national newspaper reporter Bethany Usher is now an academic at Newcastle University specialising in journalism and crime. She believes it is time for a rethink on how crime news is researched and circulated.

She is especially critical of newspapers’ shift towards clickbait content online. She believes news organisations have lost sight of their duty to preserve open justice in crime reporting. She feels this has been replaced by cheap, sensational titillation to drive online traffic, with no public interest justification.

Before I began work on my book, I gave much thought to my motive. The Carol Park case spanned five decades. She went missing in 1976, a young mother of three and her body was found in the lake 21 years later. Her husband Gordon Park was the chief suspect: in 1997 he was married to his third wife.

It had seemed an open-and-shut case. Park had the motive – it was an unhappy marriage plagued by mutual infidelity. He had the wherewithal: he had kept a boat on the lake and was a keen mountaineer proficient in tying the type of knots used to truss the body.

But Park’s insistence that he was innocent and the passage of time hampered the investigation and it would be a further two decades before the case reached its conclusion in 2020.

Two miscarriage of justice books had featured the case, promulgating the claim that Gordon Park was innocent. There followed a book by a Crown Advocate in the case who was angered by the suggestion the conviction was unsound.

But each of these publications preceded the final Court of Appeal judgement in 2020, in which Park’s conviction was upheld.

Ethics of returning to the crime

Over three decades a vast amount of public money was poured into Cumbria Police’s investigation and court hearings, including Gordon Park’s 2005 trial.

These, I felt, were my own public interest reasons for revisiting the case and writing my book, the first to tell the complete story with the Court of Appeal decision.

I therefore felt justified in writing my book. I believed Park had been guilty, but I set out to write a full, even-handed and fair account of this high-profile case.

I interviewed the lead detective, the coroner from the inquest and the family of the late Home Office pathologist. I consulted contemporary press coverage and police interviews. I sought an interview with the author of one of the miscarriage of justice books, but she declined.

The final act was to reach out to Carol Park’s family. I believe my approach was done sensitively. I received a very courteous response from her son, who had stood by his father Gordon, refusing to believe him to be a killer. He explained that he did not want to revisit the traumatic events. Neither did he stand in my way of writing the book.

I had a couple of telephone conversations with Carol’s niece, who believed Gordon Park was guilty, and she was initially happy to be interviewed. But she later changed her mind after speaking with her family. I explained that I would use interviews with her in the public domain and she did not object.

I respected the family’s decisions, and I thanked them in the book’s acknowledgements for their dignified responses.

So my conscience is clear and I believe my book is a work of responsible journalism.

In the end I cannot improve upon the words of the late, great Sir Harold Evans. Quoted in Press Gazette, he said: “I think, as a journalist, respect the dignity, freedom in intelligence, of people you’re going to be reporting on. And don’t make things up.”

- The Lady in the Lake: A Reporter’s Memoir of a Murder by Jeremy Craddock is published by Mirror Books.

The post Lady in the lake murder: Why reporter has returned to the crime 27 years on appeared first on Press Gazette.

Jeremy Craddock’s new book explores a notorious Lake District murder and the ethics of crime reporting.

The post Lady in the lake murder: Why reporter has returned to the crime 27 years on appeared first on Press Gazette.